| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Phoenix Kobe

A lesson in Disaster Recovery:

Comments on community recovery following

the 1995 Great Hanshin Earthquake, Japan.

By S.L. Donoghue, Y.O. Yan, and R.T. Irving |

|

|

|

|

| |

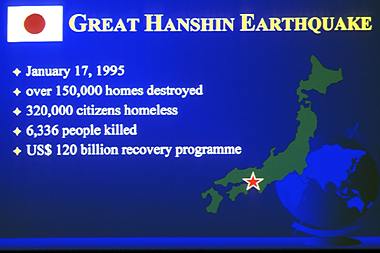

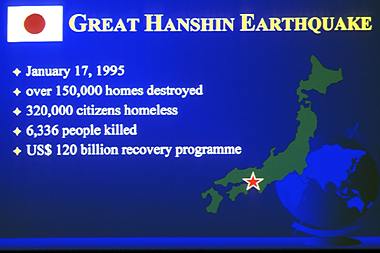

The Great Hanshin Earthquake

At 5.46 a.m. on January 17, 1995, a Richter magnitude 7.2 earthquake

struck the Kobe-Hanshin region on the southern coast of Honshu,

Japan. The epicentre was located just off the mainland, 20 km

below Awajishima (Fig. 1)

Officially named the Great Hanshin Earthquake, this event saw over

150,000 houses destroyed or burned, 320,000 residents made homeless

and 6,336 citizens killed. Kobe City lost 4,510 of it's 1.5 million

citizens, killed largely by falling debris and fires. In Kobe City's

Nagata ward, 22 separate fires, many of these infernos that started

within synthetic shoe factories, consumed over 4,000 homes and shops,

killing 600 people (Fig. 1, 2).

|

|

| |

Fig

1. Impact of the 1995 Great Hanshin Earthquake

|

|

| |

Severe structural damage

to the City's rail and road networks effectively cut off the metropolitan

area from surrounding cities and severely hampered rescue attempts;

for example several collapses of the elevated Hanshin expressway

cut the City's life lines to neighbouring Osaka and Kyoto and similarly,

collapses of the Shinkansen rail supports severed the nation's arterial

rail network.

The Response Effort

|

|

| |

Fig

2. Kobe City's Nagata ward was razed by fires. In the background

are a few temporary homes built amongst the rubble. |

| |

|

Dramatic

scenes of the devastation reached international audiences within

hours of the earthquake. For several weeks following, news of the

rescue effort, the mounting death toll and estimates of escalating

economic loss dominated world media reports, prompting not only

numerous offers of international aid, but also considerable criticism

over what was considered to have been an extremely poor government

led disaster response and handling of the crisis.

Additional unforeseen problems compounded the loss. Traffic jams,

caused by residents attempting to flee Kobe City, and the collapse

of the City's road and rail infrastructure, only added to the confusion

and hindered the movement of emergency vehicles, including, somewhat

late in the day, Japanese Military units from nearby bases.

|

|

| |

|

|

Fig

3. Structural damage to City Hall, Kobe City. Note the collapse

of one floor.

|

|

| |

|

Power

failures severely hampered treatment of the injured lucky enough

to have made it to the City's hospitals, and also rendered many

of the City's fire cistern water pumps temporarily inoperable. Many

fires were thus left unattended. To complicate matters further,

a decision to temporarily restore electricity to affected areas

and thus households in which electrical appliances had toppled over

in the earthquake resulted in many new fires.

Serious

shortcomings in the rescue effort soon became apparent. While, for

many years, residents of the Kanto region have been aware of the

imminent occurrence of a 'big one', those in the Hanshin area were

complacent to the threat of a major earthquake. Disorganised and

confused relief workers tried the best they could to minimise further

loss of life. Clearly, however, the response plan had been hopelessly

flawed from the very outset. Confusion over where the responsibility

lay for co-ordinating a response, the limited co-ordination that

existed between rescue services in neighbouring jurisdictions, a

lack of overall emergency preparedness, and limited availability

of resources severely hampered the rescue effort and left the residents

of the Hanshin region largely helpless and struggling to cope with

the enormity of their loss. Just over half of the total casualties

(3,266 residents of Kobe City) of the region died immediately, 1,397

within 6 hours; and a total of 5,047 in the first 24 hours. Had

the response been properly planned, many hundreds, if not thousands

of lives, probably would have been spared.

|

|

| |

Community

Recovery

|

|

| |

Fig

4. Close-up view of the collapsed floor. |

| |

|

Following

severe criticism of the response effort, government authorities

were determined to improve public and international perceptions

of their disaster management efforts, and consequently they swiftly

implemented projects to (a) restore the transport networks (b) demolish

damaged structures and remove debris (c) provide housing for the

homeless, and (d) distribute relief aid. The overall aim being to

return the community to a degree of normalcy within the shortest

possible time period. To this end all levels (national, prefectural

and local) of government were involved in the recovery effort (Fig.3,

4, 5).

Within

Japan itself, the first official responses came from the local (municipal)

governments who each devised their own community-specific plans

for rebuilding.

|

|

| |

|

|

Fig.

5. The damaged City Hall was demolished and a new Hall now stands

in its place. Note the structure has fewer floors!

|

|

| |

|

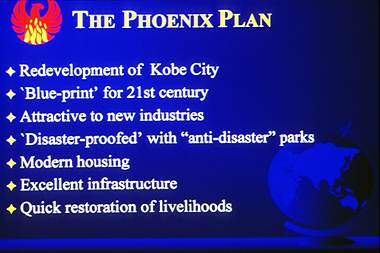

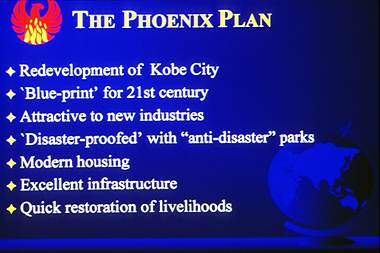

By March

1995, 17 renewal plans had been submitted. These plans were finally

embraced at prefectural level with the adoption of Kobe City's Phoenix

Plan, a $US 120 billion blueprint for rebuilding its many

communities affected by the earthquake (Fig. 6, 7).

Under this plan, 'a sparkling new city' would stand in the ashes of

Kobe. A city highly attractive to new businesses and fully earthquake-proofed.

Old and congested community areas would be redeveloped into 'showpieces'

of modern living, with wider roads, bigger parks and recreational

facilities, high rise apartment blocks, multi-cultural shopping and

residential areas, and new industrial and commercial developments.

Three aspects of recovery, and three clear priorities are identifiable.

First to be addressed were areas of national importance, these being

the major transportation links and port facilities. The second and

third priorities were, respectively, redevelopment of the 17 designated

areas, and restoration of urban areas outside of these. |

|

| |

Fig.

6 The objectives of Kobe City's Phoenix Plan

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Fig.7

Banner advertising the Phoenix Plan to Kobe City residents.

|

| |

|

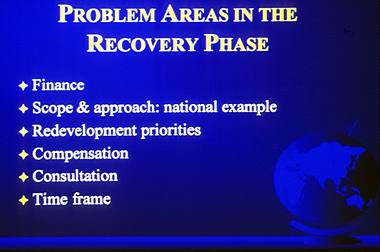

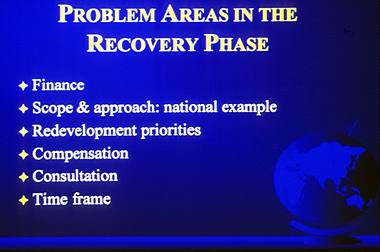

The

Phoenix Plan presents

as a wholesome picture of recovery for the Hanshin area. In

reality, however, the Plan has actually hindered recovery in many

local communities,

where the restoration of homes and livelihoods should have been a

priority. Residents describe a very different picture of actual recovery

to that presented by the government officials. Recovery at community

level has, in fact, been a long, slow, and frustrating process. Why?

The answer to this question is a complicated one, involving many issues

(Fig. 8). We can identify a number of factors that have collectively

aggravated this situation, but the major underlying reason for this

unprecedented slow recovery is government intervention, i.e. government-imposed

redevelopment plans. To demonstrate, we can look briefly at the problems

in two communities, Shinnagata and Kotoen. These two communities showed

contrasting characteristics of earthquake-related damage, and partly,

as a consequence of this, local government adopted different recovery

approaches.

|

|

| |

Fig.8 Why the recovery programmes did not adequately address community

recovery.

|

|

| |

In

Kotoen, although numerous homes suffered substantial damage, most

escaped with only slight damage (typically loss of roof tiles and

cracked walls) and so did not warrant demolition. Much of the housing

in Kotoen was 'modern', built in the 1970's or later, and built

to the more stringent, revised building codes of that time.

|

|

Fig.

9 A typical example of an old, pre-war wooden house which collapsed

as a result of shaking and added stress from the weight of the

clay-tile roof.

|

|

| |

|

As a result,

residents of Kotoen were largely left to plan their own redevelopment.

Damage to homes was assessed by government agencies, and residents

were paid compensation according to the degree of damage suffered.

If the structure was considered 'repairable', owners were allowed

to rebuild at will. Property owners were therefore able to rebuild

their community, to the same standards and style as existed before

the earthquake. Even so, serious problems emerged. Many property owners

held mortgages on their properties, and for those who lost their homes,

they were now faced with paying off their existing mortgage, on a

property that no longer existed, and raising sufficient funds to buy

a new home. The amount of monetary compensation received to help them

rebuild was considered by many to be 'insulting'. Never

the less, residents of Kotoen were given the freedom to rebuild, and

there were no government-imposed plans for redevelopment of their

community.

|

|

| |

In

Shinnagata, the majority of structures were old (pre-war) wooden

buildings (Fig. 9). Most structures collapsed under the weight of

the heavy clay roof tiles characteristic of homes of that era. Others

were razed by fires, which quickly spread, from house to house in

the cramped pre-war urban environment. Fire-fighters had at best

two hours water supply with which to fight the fires due to earthquake-induced

rupturing of underground water cisterns and rupturing of more than

200 fire hoses by passing vehicles. Few homes escaped destruction.

|

|

| |

Fig

10. A temporary pre-fabricated structure being used as a manufacturing

shop for synthetic shoes, in Nagata Ward, Kobe City. |

| |

|

Within

weeks of the earthquake, plans for rebuilding Shinnagata had been

submitted to government. By

early March, 1995, government approval was given to city planners

for a 'wholesale' redevelopment of the area. What

was left of the old pre-war housing would be demolished, and multi-storey

concrete apartment blocks would replace them. The traditional corner

stores would be replaced by neon-lit supermarkets and shopping plazas.

Residents who had lived in low-cost housing would have to buy into

expensive apartment complexes, and be forced to relocate their family

home to a new area. They would be separated from friends and neighbours,

and would be allocated housing by lottery.

The traditional shoe factories (Fig. 10), small single-story

manufacturing shops, would all be relocated into one central complex.

The relocation would, for many, result in a loss of their traditional

clientele, and generate competition amongst 'old friends' in the industry.

The traditional coffee shops and corner stores would not be able to

compete with supermarket chain prices and would lose clientele and

eventually be forced to close.

|

|

| |

|

|

| Fig.

11. Large areas of cleared land, such as this, characterised

Nagata Ward, following the earthquake and fires that razed 40%

of all structures. In the background are temporary homes, which

must eventually be torn down to make way for new developments.

|

|

| |

|

There

was an outcry, with residents calling 'foul play'. The speed with

which the plans had been approved stunned the community. Government

officials had not consulted local residents about their proposals

for redevelopment, and were largely unsympathetic to their concerns.

Compounding the problem was the amount of money the Government was

then investing into major infrastructural projects. Kobe residents

were particularly vocal regarding the Transportation Ministry's hasty

plans to build a new airport off Kobe's Port Island, at the expense

of getting peoples lives back together in the quake ravaged city.

Interviews

with government officials and city planners then revealed that plans

for urban redevelopment of Shinnagata already existed, and had existed

for some time. Indeed, all communities earmarked for redevelopment

in the Phoenix Plan correlated exactly with those areas defined in

the earlier Kobe City urban renewal plans. Shinnagata had for several

years been designated a redevelopment zone because it had long suffered

from inner city problems including aged and deteriorated buildings,

congested streets, and lack of open spaces, and because it contained

incompatible mixed land uses e.g. interwoven residential and

industrial sectors.

Did the Great Hanshin Earthquake then provide planners with a perfect

opportunity to implement these urban renewal plans, and was the Phoenix

Plan really a plan for community "recovery" or a means of

implementing existing plans? What was the motive behind the redevelopment?

It is our opinion that the Government's principal interest was urban

renewal.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Fig

12. Residents who lost their homes in the earthquake lived for

many months, and some for up to a year, in tents erected in

children's playgrounds and parks across the City. |

| |

|

Residents

were outraged at the lack of consultation and likely impact that the

plans would have on their lives. Resident's Associations were quickly

formed for the purpose of hearing and collecting resident's opinions

on the proposed plans, and forwarding their objections to government.

As the pressure for answers mounted, government officials were forced

to the table to negotiate the redevelopment, and a multitude of related

issues such as compensation and employment opportunities. As a result

of the introduction of the plans, residents were not permitted to

build any permanent structures, and indeed had to apply for a permit

to build temporary dwellings (Fig. 11), with the understanding

that any

structure would have to be demolished within a five year period, at

the owners expense, to make way for urban redevelopment. Court cases

loomed because insurance companies refused to pay for houses lost

to the fires. Those who held fire insurance were told that the fires

were a result of an earthquake, and therefore they would need earthquake

insurance in order to receive payment. Those that held earthquake

insurance were told that fires destroyed their homes, not the shaking

from the earthquake. They too were not paid. |

|

| |

|

|

Fig.

13. Re-building Nagata. Permanent structures are now allowed

to be built.

|

|

|

|

Nearly

all of Shinnagata's residents were thus forced to remain living

in temporary shelters (Fig. 12) and pre-fabricated while government

negotiated the redevelopment. Locals conducted their business from

pre-fabricated fibreglass 'boxes' laid out the along buckled sidewalks.

Both parties became locked in debate for almost two years following

the earthquake. Many residents chose to leave the area having given

up hope of ever being able to rebuild a life there.

Finally, in March 1997, three years after the earthquake, agreement

was reached between the parties, and approval was given for redevelopment

work to begin (Fig. 13).

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Fig

14. Homes in Kobe City are being built to new designs and safety

codes. Residents of Kobe hope never to experience such an earthquake

again. |

| |

|

There

will be high-rise complexes, but fewer than planned. Roads will have

to be widened to satisfy regulations concerning building height and

road width, and residents will have to relocate as land is consumed

for apartment developments. Land zoning will see areas set aside for

residential, commercial, light industrial and recreational (including

expanded parkland) uses. The revised plans primarily aim to create

a spacious living environment with a new road layout, wider tree-lined

roads, and low-rise housing. To address future safety, there will

also be a major redesigning of the underground water storage facilities

used for emergency fire fighting.

New

low-rise homes are being built using wood and/or steel (Fig. 14) on

concrete foundations. They incorporate new seismic resistant structural

features. Many of these homes have been built on a Canadian model,

and a post-earthquake feature has been the employment of many Canadian

nationals for the purpose of building of these 'earthquake-proof'

homes. |

|

| |

One

obvious impact of the redevelopment has been that the face of the

Japanese urban landscape has now changed. Gone are the bonsai gardens,

ceramic roof tops and smoky, dimly lit wooden coffee shops. Shinnagata

no longer 'feels' truly Japanese.

A memorial

wall to the earthquake will be built in Shinnagata. It will serve

as a reminder of the many thousands of friends and family members

lost. Equally important, it will be a pertinent reminder to government

of the importance of developing sound disaster-management plans, especially

disaster response and recovery plans. |

|

| |

References cited:

- Kobe Shinbun S.g. Shuppan Sentaa, 1995: The Hanshin-Awaji earthquake:

a collection of air photographs - a record of events five days

after the earthquake, January 17-21. Kobe Newspapers Group Publishing

Centre.

- National Land Agency 1995: White paper on disaster prevention

(In Japanese).

- Nishimura, K. 1995: Nothing Shakes. Look Japan (May) 4-10.

- Rafferty, K. 1995: Eastern Express 1 March 1995

- Sait_, T. 1995: The Road to Recovery. Look Japan (May)

14-15.

- The Daily Yomiuri :2 Dec. 1995, 4 December 1995, 31 December

1995, 19 February 1997, 3 March 1997.

- The Southern Hyogo Prefecture Earthquake Dammage Assessment

Support Committee 1995: A collection of aerial photographs (with

local areas labeled) of region struck by the Hanshin Earthquake

. Nikkei Osaka Pr. Incorporated.

- Walsh, J. 1996: Kobe, One Year Later. Time (January 22)

14-19

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|